Interview with Kenneth Deer

Kenneth Deer is from the Bear Clan of the Mohawk Nation of the Kahnawake territory. He is an award-winning journalist, an educator and an internationally-known Indigenous rights activist. He was also an active participant in the development of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which took 25 years to draft and was adopted in 2007 by 144 states, with the exception of Canada and four other states. He also holds an Honorary Doctorate Degree from Concordia University and was the 2010 recipient of the National Aboriginal Achievement Award.

The True History of First Nations in Canada

Written by Alexandrine Royer

1. In an interview back in 2015 with Just in Canada, you mention that the reason why people don’t know about Indigenous people in Canada is “rooted in the education system”, adding that “Canadians are not educated about Native people and we are invisible in the system”. What do you think Canadians still fail to know and understand about the history of the First Nations?

I think there is a lot that Canadians still don’t know and understand about the history of the First Nations. The results of the Truth & Reconciliation led to a series of recommendations in education to address the legacy of the residential schools. But the education in our Canadian schools is still woefully inadequate. Schools have to be adjusted to take into account the history of Indigenous Peoples. This includes the history of indigenous people and their relationship with Canada before the first contact and up until the present.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was a call to action which a lot of post-secondary institutions have taken that to heart. Colleges and universities are putting more materials and courses about Indigenous People in Canada. Since I made that statement back in 2015, there have been improvements, but we still have a long way to go.

History books mention Indigenous People were here during the first contacts and colonization, but we then disappear and nothing is said about us after Confederation. Indigenous People were not invited in the Charlottetown meetings that created Canada, the people in government at the time were not interested in having Indigenous people involved. It was a European settler institution and continues to be so today.

Today you hear about the clearing of the plains (see the book by James Daschuk) and how John A. MacDonald negotiated land treaties, what they did was starve the Indigenous People in the prairies into submission. These events are well-documented and should be in the history books but are not.

One of the fundamental racist issues goes back to the whole era of discovery. The doctrine of discovery refers to the papal bulls that were issued after Columbus stumbled onto the American continent. European kingdoms asked themselves, what do we do with all these people that are there. In 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued a papal bull that decreed that if you find any new people, and if they are not Christian, you can claim all that land for your king. This papal bull gave the political, legal and moral justification for Spain, Portugal, France and England to claim the American continent on behalf of their king. This is the underlying relationship that is the basis of all Indigenous exploitation and disempowerment. It also explains why everything is called crown land- even today-, it was claimed for the French king or the English king.

These papal bulls are still in effect and they have not been revoked by the Vatican, despite contestations. In courts today and in recent history, Canadian and American governments have used the doctrine of discovery to state that they own the land. It may have taken place hundreds of years ago, but this history still has contemporary implications, governments have continued to use it as a legal defence in court cases against Indigenous people. It is a fundamental racist position because it states because we (the First Nations) are not Christian, we have no more rights than the animals. Racial superiority and European supremacy are at the basis of this relationship.

When I was in elementary school, I was educated under the Indian Act and the goal was to assimilate us. The only thing I remember learning about the Mohawks is that we burned Jesuits at the stake and were responsible for the Lachine massacres. When you are an impressionable kid, this can have a big effect on you. What they were forcibly teaching us was not our history, our culture and our language. We were taught that Jesuits were the martyrs and heroes and we (the First Nations) were the bad guys, especially the Iroquois. In actuality, all we were doing was to defend our territory, we were not willing to come under either the French or English king.

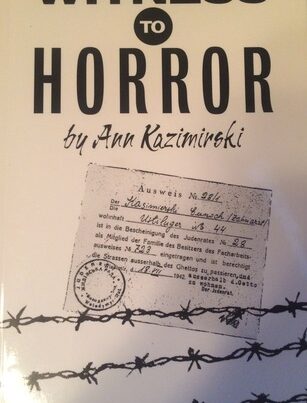

2. It was only in my final years of university that I learned about Canadian civil servants like Duncan Campbell Scott, who ran the residential school system and once described the policy of the Indian department as being “geared towards the final solution of our Indian problem”- a term that was then used by the Nazis for the Jews in Europe. Why do you think it is important that the history of the First Nations be taught alongside these other genocides?

I think it is important because it was one (a genocide). If you want to teach history, you cannot think of Rwanda and the Holocaust as being the only ones, there were others and North America is an example. It was a deliberate act by the Canadian government, it is a genocide and it is a part of Canada’s history. The Indian Act is still there today, we still suspect that the long term goal is for Indigenous People to disappear. It is genocide without gas chambers and mass graves.

When teaching about the genocide against the First Nations, you have to include the doctrine of discovery, which as I mentioned is still used today in courts. It might have been a whole different situation if the Pope and people hadn’t followed that, we might have a relationship that is very different today. The Indian Act (the piece of legislation which introduced the residential school system) also needs to be explained, with all the awful rules it legislated against the First Nations. We couldn’t go to court for land claims; lawyers could be disbarred or arrested if they tried to represent and defend us. From 1927 to 1956, we were systematically denied justice in the court system. We were not allowed to make claims before – it was illegal (First Nations were also denied the right to vote).

When we hear now about lawsuits against the government, people often ask me how come this wasn’t settled before? The answer is it was because it wasn’t allowed up until recently. They (the Canadian government) knew that we were in our rights and that they would lose in court. It was done so that they could keep all the land and natural resources. Canada’s wealth is based on stolen land and stolen resources. It was taken immorally from our people because we weren’t treated as equals. It goes back to white European believing in their superiority over Indigenous Peoples.

Duncan Campbell Scott- Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932

3. With the Truth & Reconciliation Commission and the report of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Canada is very slowly beginning to recognize its history of state practices that were intended to eliminate Indigenous peoples and destroy communities through forced assimilation. Are you willing to share your own family or community’s experience of state violence? How is it still felt today? How did you resist?

My parents also went to government schools under the reserves. The whole process started in the 1800s, the goal to assimilate Indigenous People goes back to a long time ago.

Before, we had our own Indigenous teachers who were then fired by the government. The Indian Department brought in the Sisters of Saint-Anne. They brought in nuns from New England into the Catholic schools to teach us English. It was a policy from Ottawa to make sure that we spoke English and not French so that we wouldn’t be allied with the French Canadians. It was a purposeful action by the government to make sure we didn’t come too close. I only found this out recently during a presentation done by Wahéhshon Shiann Whitebean at Concordia University.

The people who kept our language were the ones who dropped out of the schools. They were brought up in the language and often they would quit school as they were needed on the farm and would stay home. 40 years later, they are the ones who saved our language and who we hired to teach it in schools.

I can’t speak with authority about the experience of other Mohawks across the border, but assimilation through the school system was common throughout North America. In the 70s and 80s, we started to teach our language in our school system. Not every community can do that, many have to send their kids outside because their population is not big enough to have their own schools.

4. The Ontario Human Rights Commission documented how Indigenous people experience racial profiling in policing and federal correction systems, child welfare, health care, education, retail and private business, government and social services and housing, and so on. What are some examples of everyday racism and/or harassment that you or those close to you have suffered?

I just wrote a story on Facebook describing how when I was a boy, I was denied the right to speak my language, to know my history and to learn and live my culture. I went to the Indian day schools, but the curriculum was the same as the residential schools. I was torn from and wasn’t allowed my culture, language and history. I was a victim of that genocide and it has affected my life. I knew I was Mohawk, but I didn’t know what it meant. I didn’t learn anything about it in college or university. I had to learn from elders and from people who were not assimilated.

Despite my efforts, I never did learn my language, I was only taught English. It was an early experience of racism and I struggled with it in high school. Back then, I had a hard time defending myself when people asked me what it was to be Mohawk. I would come up with assumptions that weren’t rooted in history or truth.

An elder one time said I was an incomplete person and I have to say that statement stung. I didn’t have everything that I was supposed to have, it was taken away from me. I felt inadequate in explaining who I was and unable to be who I was. Today I am still learning what it means to be Mohawk. Fighting for our identity, it is a journey that life has sent me.

One of the big debates internationally still is whether or not Indigenous People count as a people. In 1987, the first time I went to Geneva was when we were working on the first draft of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People. At the time, the big issue being debated was that Indigenous People were not people like other peoples. We had no control over our land, our territory, our own governance. Whether or not we were a people, that was the fundamental point that the government of Canada was questioning. In international law, all peoples have a right to self-determination. Canada was arguing that Indigenous People are communities, tribes, bands, or clans- they were not considered peoples. We had to fight hard to be given the legal recognition that we are equal to all other peoples.

A lot of racism that I experienced happened in my younger years. I got called names like dirty Indians and other derogatory insults. With the missing and murdered Indigenous women, the reason why it took so long for the Canadian government to act is that Indigenous women are seen as being worth less than a white woman. It is a clear sign in today’s society that there is still racism, why so many indigenous women are missing at a higher ratio and why so many cases remain unsolved. When police went on a search for Robert Pickton, a serial killer in BC, it had to take a shocking thing like that to bring attention to all the Indigenous women that were being murdered or were going missing. He could have been caught years before, it just wasn’t worth as much (to the police) because of who his victims were.

There are still plenty of other examples. Look at the law enforcement in Val d’Or, wherein 2016 there were 37 cases of police abuse against Indigenous women, including coercing them into sexual advances and other forms of sexual violence. The physical wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples continues to be at great risk. There was another recent case in Alberta this year when Jake Sansom and Morris Cardinal, two Métis who had gone hunting, were shot and killed after being ambushed. Before that, there was the murder of Colton Boushie. There are more of these types of incidents than people think they are.

5. In that same interview in 2015, you mention that the issue with Indigenous peoples in Canada is not just about race, but that your rights as a people, especially to self-determination and to lands and territory, are not recognized. What do you see as being the first steps to ensuring the equal treatment of the First Nations?

I think that the UN declaration is a good place to start . Everyone should read it and see the rights of Indigenous peoples. They will see that those rights are just the same as the rights of any other peoples, just from an Indigenous perspective. It includes the right to own spirituality and to our own medicine and health practices, these are the types of rights that everyone else takes for granted. Indigenous people were forced underground and we couldn’t practice our own religions. We also have the right to our own governance system. In the Mohawk nation, we have our own clan system and that is based on a matrilineal organization. We have a clan mother and chiefs. We have a political system in operation that predates European contact.

People often say that Indigenous People need to be decolonized. Canada is still colonizing Indigenous People and we have to decolonize. It (to decolonize) means different things to different people. For me, it means Indigenous people must see themselves and be recognized as a sovereign people. If you believe you are sovereign, then you can start to act like you are sovereign. We are not here to destroy Canada, but in reverse Canada should not be trying to destroy us. We must learn to live on the same piece of land which is ours.

I have started to use another term, that of counter-colonization. We have to counter the colonization process that has been laid against us. When we start to decolonize our minds and start thinking like Indigenous people, we can then start to counter the legislation and measures still in place to assimilate us.

When it comes to education, Indigenous and non-Indigenous education are two different things. As Indigenous people, we have to control our own education. At Kahnawake Survival School, we teach all the basics and our culture and our language. You have to pass Mohawk in order to obtain your high school diploma. The name of our school is clear, we have to be in control of our own education in order for Mohawks to survive. We decide what information we pass from one generation to the next.

For non-Indigenous Peoples, the goal is for them to understand our history in a non-racial way. We have to counter the racial European superiority that is engrained in the education system. For every phase of Canada’s history, in every school, there has to be a component that details what was the situation of Indigenous People during that time period. You cannot skip over what were the relations between the colonizers and the Indigenous people throughout Canada’s history and just address it from a European colonial point of view. You need to include all perspectives on those relationships and events, you have to learn the Indigenous perspective on what we were experiencing and what kind of relationships we had. You also have to allow Indigenous people to give that perspective.

UN poster for the 10th anniversary of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples